When it comes to any form of horticulture then I am there. I am what you call a keen gardener. Yeah I know, sounds crazy for a guy but it’s this passion I have for beauty in the floral world of Indonesia. There are numerous botanical gardens in Indonesia including an excellent one at Candikunung on the island of Bali.

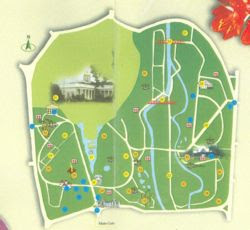

The ultimate in botanical gardens, however, had to be the Bogor Botanical Gardens located 60 km south of the capital of Jakarta in Bogor. Covering more than 80 hectares, it adjoin the Istana Bogor or Presidential Palace.

The Gardens are also a major centre for botanical research. The garden contains more than 15,000 species of trees and plants, 400 types of palms as well as orchid houses that contain some 3000 varieties. Put these together with flowing streams and lotus ponds and you have a botanical garden worthy to match any other in the world.

Recently, expat resident of Jakarta Simon Marcus Gower wrote this small article about the splendour of the Bogor Botanical Gardens:

It is often said that when things are practically on our doorstep, we can have a tendency to overlook them and not truly appreciate them for what they are.

This is perhaps true of the excellent Bogor Botanical Gardens, which is close to Jakarta and so perhaps not as fully appreciated as it should be.

For example, acquaintances have cited how they see the gardens as not much more than a kind of “major traffic island in the center of Bogor”, because of the way in which Bogor’s traffic congestion circumvents it.

Others can be complainants and dismissive of the great gardens because of “the masses of people” that visit on weekends or national holidays. But even when the “masses” do enter the gardens, the sheer size of this splendor in the center of the city still means that quiet and secluded parts can be found.

The gardens’ size is impressive too. Though roads encircle the park, at 87 hectares the Bogor Botanical Gardens is unquestionably the predominant and preeminent feature of the city.

But how did this wonderful place come to be, and why are we still able to appreciate them nearly 200 years after they were first established?

The first question can lead to some debate, as some will credit Sir Stamford Raffles as providing the inspiration and the instructions to begin the gardens. More widely credited as the “founding father of the gardens” is German botanist Professor Reinwardt.

There is now a stone monument within the gardens that identifies Reinwardt as its founder. Its plaque indicates that in 1817 at the behest of then Dutch governor-general Van de Capellan, Reinwardt was commissioned to establish the gardens. Along with colleagues from England’s Kew Gardens, Reinwardt began the green, landscaped expanse that we see today.

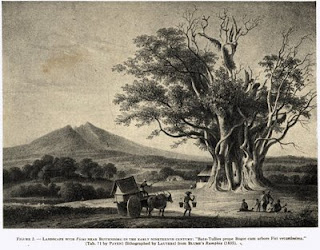

The gardens is indeed a tribute to the vision of those men: Its avenues of palm trees provide stunning vistas; its collections of exotic plants create labyrinthine intrigue; the matured, skyscraping trees are a spectacular sight; and botanical wonders assail the eye throughout.

The design of the gardens seems to combine the manicured and ordered seriousness of formal gardens with the more chaotic and free areas of almost overgrown wilderness. The latter surrounds the relatively small portion of the gardens known as the Dutch Cemetery.

Here, hidden in a secluded part of the gardens, sit some 42 graves dating back to Indonesia’s colonial past. Sheltering these graves are massive bamboos that crowd around in a seemingly disordered manner.

The presence of the bamboo, however, creates a remarkably — and appropriately — peaceful corner. The graves are remarkable too, in both their ages and those that they commemorate. In fact, some even predate the gardens.

Among those marked here in their final resting place are Dutch governor-generals and the biologists who worked in the gardens. There is even a relatively recent grave: that of Dutch botanist Professor Kostermans, who requested that he be buried among “the plants and environment that he loved”, which was duly carried out in 1994.

Not too far from the Dutch Cemetery is another commemoration of a European resident of the archipelago. This monument to the memory of Olivia Raffles, the wife of Sir Stamford Raffles, is a delicate, domed and colonnaded dedication to an evidently beloved wife.

The inscription of the monument tells much of the love that was felt, as well as the age in which it was written: “Thou who ne’er my constant heart one monument hath forgot, tho’ fate severe has bid us part yet still — forget me not”.

These are perhaps some of the more romanticized and artistic aspects of the gardens, but it also possesses commercial and scientific aspects that add to its significance, both historically and presently.

The Bogor Botanical Gardens achieved world renown for the research conducted within its premises, notably on the local cash crops of coffee, tea and rubber — not to mention tobacco. In conducting such activities, the gardens was significant in helping to develop and to realize the success of the country’s plantations.

Its plants and trees also highlights the great significance of the gardens. With an estimated collection of more than 15,000 species of plants and trees, including some 400 different types of palm and an greenhouse containing thousands of orchid varieties, the gardens’ collection is nothing short of extensive and impressive.

The range and variety of things to see in the Bogor Botanical Gardens can make for an excellent day trip. From huge trees with spectacular buttress roots firmly holding them in the ground, to broad, sweeping lawns, and from avenues of trees to lakes, ponds, streams and a river running through its center, there is much to take in.

While simple bridges allow for views onto a river strewn with rocks and boulders, it is the red suspension bridge that offers the most excitement: people crossing it bounce along as its suspension cables swing and take up the strain.

Any visit to the Bogor Botanical Gardens will mean a direct and enjoyable encounter with natural splendor. The gardens represent simultaneously a better side to the colonial past as well as the natural tropical wonders that are to be found within the Indonesian archipelago and beyond.

The modest entrance fee allows for a good day out and the possibility of contributing to the maintenance of this natural treasure trove of Indonesia — said to be among the best gardens in the world.

The ultimate in botanical gardens, however, had to be the Bogor Botanical Gardens located 60 km south of the capital of Jakarta in Bogor. Covering more than 80 hectares, it adjoin the Istana Bogor or Presidential Palace.

The Gardens are also a major centre for botanical research. The garden contains more than 15,000 species of trees and plants, 400 types of palms as well as orchid houses that contain some 3000 varieties. Put these together with flowing streams and lotus ponds and you have a botanical garden worthy to match any other in the world.

Recently, expat resident of Jakarta Simon Marcus Gower wrote this small article about the splendour of the Bogor Botanical Gardens:

It is often said that when things are practically on our doorstep, we can have a tendency to overlook them and not truly appreciate them for what they are.

This is perhaps true of the excellent Bogor Botanical Gardens, which is close to Jakarta and so perhaps not as fully appreciated as it should be.

For example, acquaintances have cited how they see the gardens as not much more than a kind of “major traffic island in the center of Bogor”, because of the way in which Bogor’s traffic congestion circumvents it.

Others can be complainants and dismissive of the great gardens because of “the masses of people” that visit on weekends or national holidays. But even when the “masses” do enter the gardens, the sheer size of this splendor in the center of the city still means that quiet and secluded parts can be found.

The gardens’ size is impressive too. Though roads encircle the park, at 87 hectares the Bogor Botanical Gardens is unquestionably the predominant and preeminent feature of the city.

But how did this wonderful place come to be, and why are we still able to appreciate them nearly 200 years after they were first established?

The first question can lead to some debate, as some will credit Sir Stamford Raffles as providing the inspiration and the instructions to begin the gardens. More widely credited as the “founding father of the gardens” is German botanist Professor Reinwardt.

There is now a stone monument within the gardens that identifies Reinwardt as its founder. Its plaque indicates that in 1817 at the behest of then Dutch governor-general Van de Capellan, Reinwardt was commissioned to establish the gardens. Along with colleagues from England’s Kew Gardens, Reinwardt began the green, landscaped expanse that we see today.

The gardens is indeed a tribute to the vision of those men: Its avenues of palm trees provide stunning vistas; its collections of exotic plants create labyrinthine intrigue; the matured, skyscraping trees are a spectacular sight; and botanical wonders assail the eye throughout.

The design of the gardens seems to combine the manicured and ordered seriousness of formal gardens with the more chaotic and free areas of almost overgrown wilderness. The latter surrounds the relatively small portion of the gardens known as the Dutch Cemetery.

Here, hidden in a secluded part of the gardens, sit some 42 graves dating back to Indonesia’s colonial past. Sheltering these graves are massive bamboos that crowd around in a seemingly disordered manner.

The presence of the bamboo, however, creates a remarkably — and appropriately — peaceful corner. The graves are remarkable too, in both their ages and those that they commemorate. In fact, some even predate the gardens.

Among those marked here in their final resting place are Dutch governor-generals and the biologists who worked in the gardens. There is even a relatively recent grave: that of Dutch botanist Professor Kostermans, who requested that he be buried among “the plants and environment that he loved”, which was duly carried out in 1994.

Not too far from the Dutch Cemetery is another commemoration of a European resident of the archipelago. This monument to the memory of Olivia Raffles, the wife of Sir Stamford Raffles, is a delicate, domed and colonnaded dedication to an evidently beloved wife.

The inscription of the monument tells much of the love that was felt, as well as the age in which it was written: “Thou who ne’er my constant heart one monument hath forgot, tho’ fate severe has bid us part yet still — forget me not”.

These are perhaps some of the more romanticized and artistic aspects of the gardens, but it also possesses commercial and scientific aspects that add to its significance, both historically and presently.

The Bogor Botanical Gardens achieved world renown for the research conducted within its premises, notably on the local cash crops of coffee, tea and rubber — not to mention tobacco. In conducting such activities, the gardens was significant in helping to develop and to realize the success of the country’s plantations.

Its plants and trees also highlights the great significance of the gardens. With an estimated collection of more than 15,000 species of plants and trees, including some 400 different types of palm and an greenhouse containing thousands of orchid varieties, the gardens’ collection is nothing short of extensive and impressive.

The range and variety of things to see in the Bogor Botanical Gardens can make for an excellent day trip. From huge trees with spectacular buttress roots firmly holding them in the ground, to broad, sweeping lawns, and from avenues of trees to lakes, ponds, streams and a river running through its center, there is much to take in.

While simple bridges allow for views onto a river strewn with rocks and boulders, it is the red suspension bridge that offers the most excitement: people crossing it bounce along as its suspension cables swing and take up the strain.

Any visit to the Bogor Botanical Gardens will mean a direct and enjoyable encounter with natural splendor. The gardens represent simultaneously a better side to the colonial past as well as the natural tropical wonders that are to be found within the Indonesian archipelago and beyond.

The modest entrance fee allows for a good day out and the possibility of contributing to the maintenance of this natural treasure trove of Indonesia — said to be among the best gardens in the world.